The amount of financial aid Columbia offers its incoming undergraduates has nearly doubled since the University adopted a “need-based, need-blind, full-need” approach for Columbia College and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences students in 2008, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

The data, which Columbia is mandated to report due to the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008, shows that over the past decade, the net price—the total cost of attending Columbia after grants and scholarships are subtracted—for middle- and higher-income students has steadily decreased. Yet, the net price for low-income students has steadily risen.

The NCES data describes financial aid for first-time, full-time (FTFT) undergraduates who received federal aid at CC,SEAS, and School of General Studies. Unlike the other two, General Studies does not have the financial resources to take a need-blind, full-need approach.

The following interactive graphic looks at average net prices at Columbia across the five income brackets over the last decade.

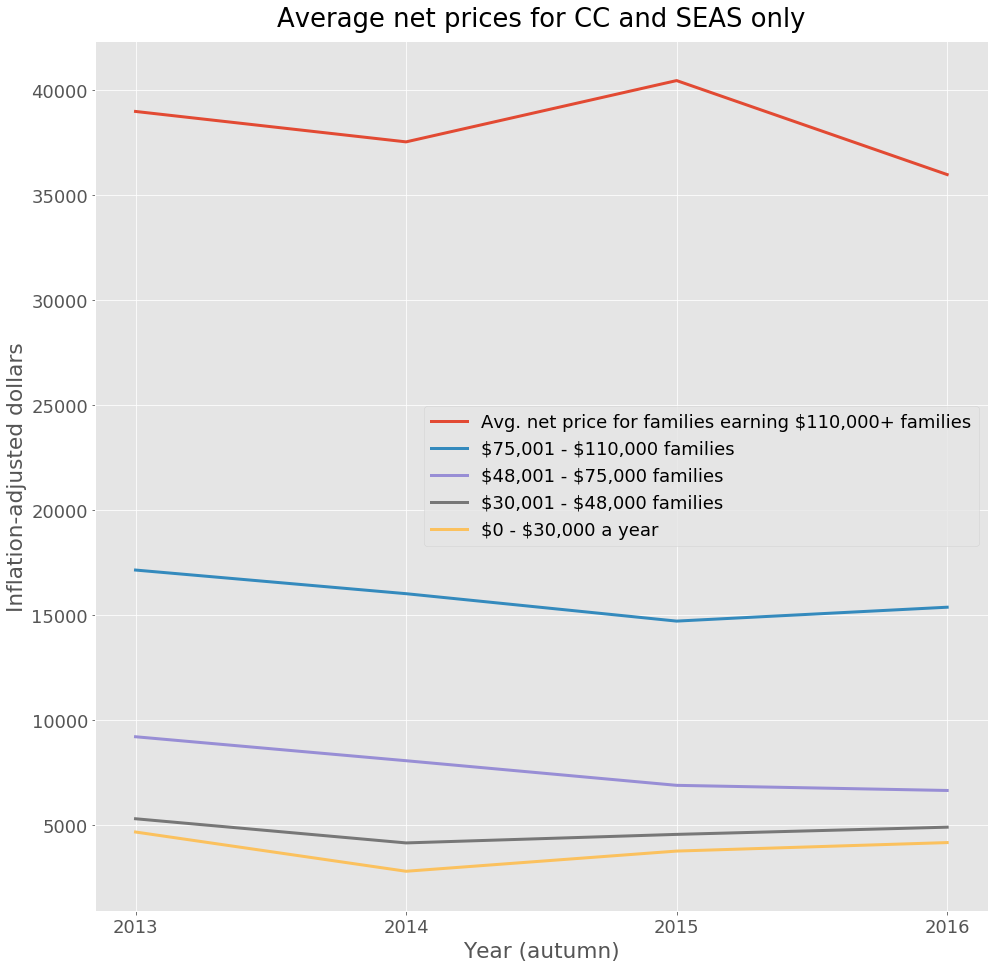

Net price data provided by the University hints at a possible driver of these inequities: General Studies. The data shows that net prices for only CC and SEAS do not exhibit the same disproportionate trends that the federal data, which includes GS, show.

Reflecting on broader trends in higher education, researchers also point to several external reasons why students from wealthier backgrounds may receive more aid—most notably, tax breaks that disproportionately benefit higher-income households.

In 2015, the Congressional Research Service found that over a fifth of tax deductions given under the American Opportunity Tax Credit went to households earning more than $100,000 a year, compared to 30 percent of households earning less than $30,000.

Another tax benefit—the 529 college savings plan—offers extensive tax and financial aid benefits. Yet a survey conducted by the financial services firm Edward Jones revealed that less than one in five households earning under $35,000 a year know about these deductions, compared to nearly half of all households that earn over $100,000 a year.

This disparity is part of a larger informational divide between students in inner-city schools and students at private and suburban schools. A national study conducted by the National Association for College Admission Counseling revealed that students at urban schools were much less likely to have spoken to a college counselor than those at suburban and private schools.

Education tax benefits can certainly assist middle- and higher-income families—especially at expensive private institutions like Columbia.

“The purpose of the tax credits was to make college more affordable for middle-income students,” Stephen Burd, a policy analyst at the New America Foundation, noted in an interview for The Hechinger Report. “The problem is that the tax credits are going beyond the middle class.”

Nevertheless, the data do not point to specific internal factors that could have caused the net price cutbacks to favor higher income ranges.

“I know people don’t often think that there’s a bottom line, but there is. And so do we help more people with less money or do we help less people with more money?” Director of Financial Services at Ithaca College Lisa Hoskey said for The Report.