Arts and Entertainment | Art

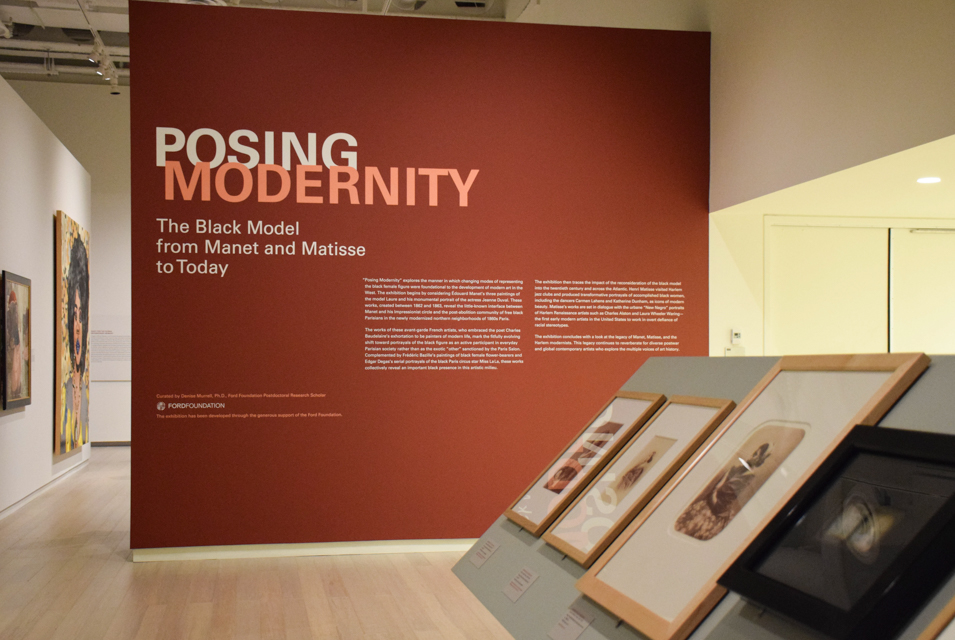

“Posing Modernity” at Wallach gallery reimagines the black female historical narrative

By Athena Chin / Staff Photographer"Posing Modernity" traces the figure of the black female throughout the history of art.By Ruba Nadar and Esterah Brown • November 2, 2018 at 3:20 AM

By Ruba Nadar and Esterah Brown • November 2, 2018 at 3:20 AM

“Posing Modernity,” the newest exhibition in Columbia’s Wallach Art Gallery, breaks away from curatorial tradition by transcending the artistic norms of gender, sexuality, and race.

The exhibition is currently on display at the gallery in Columbia’s newly opened Lenfest Center of the Arts, where it will be on display until Feb. 10, 2019. The exhibition will then move to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it will remain until July 14, 2019, under the name “The Black Model: From Gericault to Matisse.”

Curated by Denise Murrell, Ph.D. and Ford Foundation postdoctoral research scholar, the exhibition reimagines the representation of the black female figure in art while giving a voice to the marginalized individuals typically left out of historical narratives, such as those of the Harlem Renaissance.

“We see the artists of the Harlem Renaissance who are often omitted from records of modern art, but who were the first organized school of modernist artists who made it a project to move away from stereotyping and racism and [to] portray the new urban black—the new negro, to use the terminology of the day—in elegant portraits that deliberately refused the common perceptions of African Americans in popular culture,” Murrell said.

Much of the exhibition is inspired by Édouard Manet’s 1863 “Olympia,” which Murrell first came in contact with during a general art history course at Hunter College.

Murell described her memory of the course: Her professor went through the slideshow, pausing on “Olympia,” one of Manet’s most controversial paintings. The painting depicts a naked white woman, widely believed to be a prostitute, lying across a bed; a black woman stands behind her with a basket of flowers. It was the first image of a black woman that had featured in the course.

“He goes through the whole narrative of the prostitute … and then the slide flips,” Murrell said. “I thought, ‘Okay, is he going to say something that I'm not going to be comfortable with in terms of his racial interpretation of the figure?’ But it bothered me more that he didn't say anything at all.”

Distraught and confused by the lack of conversation surrounding the black servant figure in “Olympia,” Murrell decided to write her 2013 dissertation on race and modernity in Western art, as well as curate an exhibition dedicated to the subject, which became “Posing Modernity.”

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are greeted with Manet’s “La Négresse (Portrait of Laure),” and numerous other works depicting the black female figure in 19th century Paris.

“I’m looking at Manet, specifically his iconic painting, ‘Olympia,’” Murrell said. “More broadly, the fact that many of [his] images were of women of color in 1860s Paris, and [he] made those images in a way that represent a ... growing black presence in Paris ... just 15 years after the final French abolition of territorial slavery.”

The exhibition progresses into the United States, covering the Harlem Renaissance. Murell also considered a feminist perspective while curating this landmark exhibition. As the exhibition progresses through history, the self-ownership of the female figure grows simultaneously. Beginning with the stereotypical interpretations of the “black nanny,” and ending with bold, contemporary expressions of the ownership of the female body, “Posing Modernity” exemplifies an expansion in black female representation in the 21st century.

The exhibition also examines the progression of gender from the 1860s Paris salon to the contemporary, monumental images by Mickalene Thomas. The objectification of the female body is brought into question as several contemporary artists flip the narrative of “Olympia” and reimagine the prostitute as the black figure and the servant as the white figure.

“All of the paintings in this room ... present portraits of the black female figure in a manner of style, of self-confidence; sensuality, yes, but sensuality that they have complete control over,” Murrell said.

The overarching message of both the exhibition and Murrell’s vision for “Posing Modernity” is the hope that art history, and its future students, will work to tell the narratives of the oppressed.

“Join in this effort to broaden the field,” Murrell said. “Take on all of the marginalized and forgotten aspects of art history.”

More In Arts and Entertainment

Editor's Picks